HISTORY OF DARJEELING

A hundred years ago the mountain spur, on the slope of which the hill station of Darjeeling now stands formed a part of the independent kingdom of Sikkim and was covered with dense forest. The town of Darjeeling alone now contains a population of nearly thirty thousand people of many different creeds and races, but there were not more than two hundred inhabitants in the whole stretch of the mountains of this neighbourhood when, the East India Company, which then controlled British interests in India, first came into contact with it.

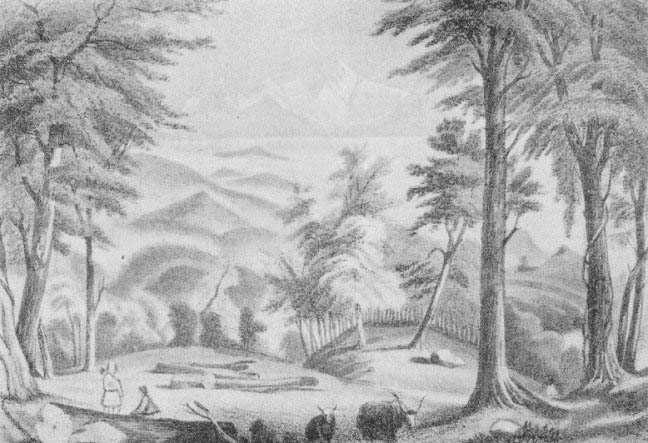

Kinchenjungha from Darjeeling

Reproduced from Sir Joseph Hooker's "Himalayan Journals," 1854

This was in 1814 when the Company intervened in favour of Sikkim against the war like Nepalese, who would otherwise have absorbed the whole of the little State of Sikkim and annexed it to their own territory. The Nepalese were repulsed in the war that ensued, and the Rajah of Sikkim was reinstated in possession of his kingdom.

During negotiations consequent on this intervention by the Company, the British representative, General Lloyd, was struck with the suitability of the spur, on which could be descried in the forest the few huts of Darjeeling village, as a sanitarium for British troops. And so, in 1835, we find the East India Company obtaining the lease of a small strip of country in the south of the Sikkim Himalaya for the purpose of a sanitarium and an outpost of strategical importance, on the northern frontier of India. A member of the Indian Medical Service, Dr. Campbell, was appointed Agent of the tract leased, and Lieut. Napier (afterwards Lord Napier of Magdala) set to work to fell the forest and lay the foundations of the hill station of Darjeeling. This officer also built the first road from these hills to the plains, a road which is still existing but which was later superseded by a much better road of which further particulars will be found here below.

The little town founded by these two officers of Government grew very rapidly, natives of the surrounding country were quick to avail themselves of the blessings of life under the egis of the Pax Britannica, and within ten years, between 1839 and 1849, the population rose chiefly by immigration from 100 to about 10,000 persons, a truly remarkable tribute to the East India Company and the administration of their officers.

This rapid growth, however, excited the jealousy of the Maharaja of Sikkim, or rather of his Prime Minister, and when Dr. Campbell and the eminent explorer and naturalist, Sir Joseph Hooke, were touring in Sikkim in 1849, with the permission of both Governments, they were suddenly seized and imprisoned. Many indignities and even severe insults were thrust on the British Agent during weeks, of meaningless detention, and as a result the usual expeditionary force had to be sent to teach good manners to the uncivilized authorities in Sikkim. Fortunately there was no necessity for bloodshed, and after the Company's troops had crossed the Rungeet river into Sikkim hostilities ceased. Consequent on this trouble, and a further ebullition of misconduct on the part of the Sikkim authorities a few years later, the mountain tracts now forming the district of Darjeeling became a portion of the British Indian Empire, and the remainder of the kingdom of Sikkim became a protected State.

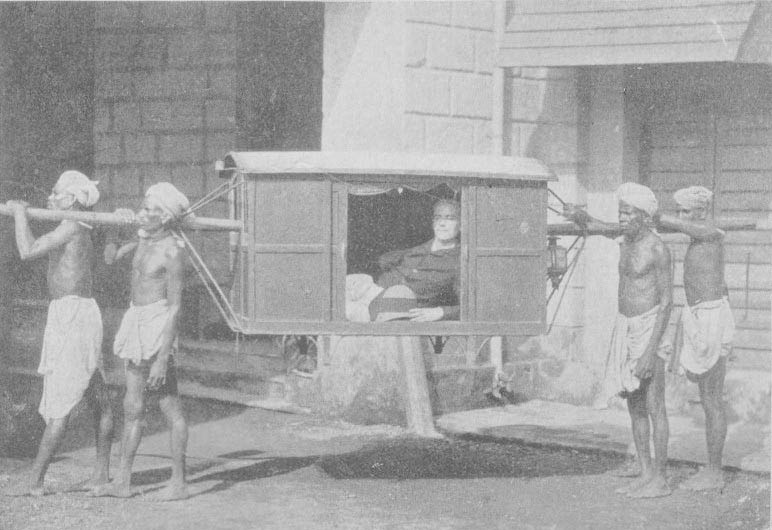

The march of progress and civilization in the mountains of the annexed territory now became very rapid. The road built by Lieut. Napier was found to be of too steep a gradient and too narrow for wheeled traffic, and so, in 1861, a new and excellent cart road with an easy gradient was commenced. This road connected with a great road that had been built across the plains of Bengal for over a hundred and fifty miles from the station of Sahebganj on the East Indian Railway, for in those days no railroad existed from Calcutta to the northern confines of Bengal. Then, indeed, the traveller had to approach the hill station by a long, roundabout route, first by rail for over two hundred miles, then by boat, palki, and pony for another two hundred miles and more, his journey taking about a fortnight instead of the twenty hours now required.

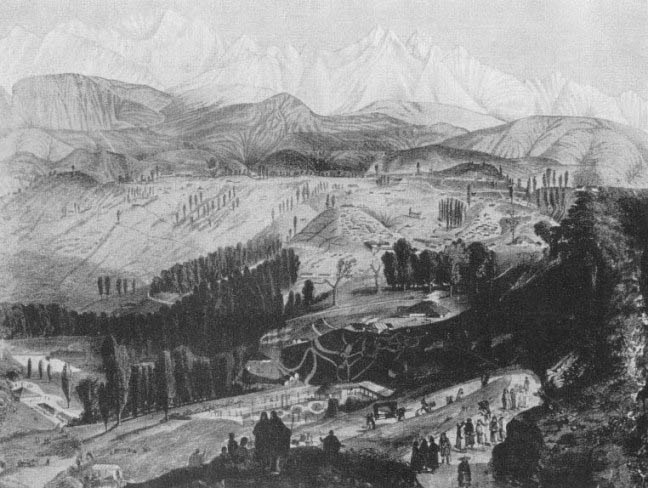

Old Darjeeling

But by 1878 a railway had been completed from Calcutta to Siliguri, almost to the base of the Himalayas, and a tonga service took travellers thence up the hill portion the journey. The cultivation of tea had by this time developed remarkably and the industry had become firmly established. But the needs, of the industry and the inconvenience suffered by the general ascent by tongas soon led to dissatisfaction with this means of transit, and to the inception of the laying of a steam tramway along the road from Siliguri to Darjeeling. This tramway was commenced in 1879 and in a couple of years was completed and developed into the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, the progress of which will be traced in the next chapter. In this way communication by rail between Calcutta and Darjeeling was established within fifty years after the forest clad Darjeeling spur of the Sikkim Himalaya came to be embodied in the British Indian Empire. And now the district of Darjeeling, which less than a century ago was principally covered by virgin forest and supported only a few hundred inhabitants, contains a population of a quarter of a million of Indians and several thousand Britishers, and a great thriving tea industry worth millions of Pounds.

A Palki